Development of the human eye

A brief overview

The ability to see is an amazing journey that starts from the process of fertilization (during embryonic development) to the first few months of life (post-natal). When a baby leaves the dark, quiet, and comfortable environment of the womb and enters the bright world we live in, what can they see? From birth, babies are able to blink in response to light and develop the ability to follow moving objects.

Vision is closely linked to brain development and as a baby’s brain matures, so too does their eyesight. The following sections will discuss about how the structures needed for sight develop, the key visual milestones of a baby, and some frequently asked questions about a child’s vision. For understanding purposes, kindly note that from conception till birth, a baby is called an embryo and after the 8th week till birth, a foetus.

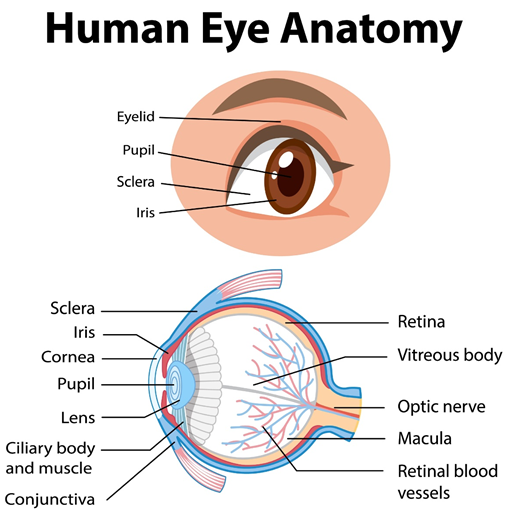

Some basic structures of the human eye

Figure 1. Structures of the human eye (Shutterstock, 2021).

In order to ease your understanding in the following sections, here are some brief definitions of the basic structures of the human eye:

• CORNEA : the transparent thin layer that covers the front portion of the eye

• IRIS : the coloured tissue at the front of the eye

• PUPIL : the dark spot at the centre of the eye. In bright light, the iris expands and the pupil gets smaller, reducing the amount of light entering the eye. In low light, the iris shrinks and the pupil gets bigger, allowing more light to enter the eye

• LENS : as light enters the eye, it hits the lens, which sits behind the pupil and functions to direct light towards the back of the eye. The lens is responsible for the “focusing mechanism” of the eye, producing clear vision

• VITREOUS : the transparent jelly located behind the lens that fills the eyeball

• RETINA : the light sensitive tissue at the back of the eye that contains millions of light sensitive cells called rods and cones. Rods allow us to see in dim light and cones allow us to detect and distinguish colour

• MACULA : the area of the retina that allows us to enjoy clear central vision and colour

• OPTIC NERVE : the structure that sends all visual messages to the brain, producing clear vision

The development of the eye in the womb

The first trimester (conception to 12 weeks)

The eyes begin to develop during the 17th day of pregnancy. In the womb, the embryo’s eyes start out as two tiny extensions from the developing brain.

At 6 weeks of pregnancy, the embryo’s eyes begin to fold inward and form 2 cup-like structures. As they grow, these structures stay connected to the brain by a stalk that eventually houses the optic nerve. The retina and lens then begin to develop.

By 4 to 5 weeks of pregnancy, the lens becomes visible and by week 7 to 8, it grows to the size that it will be at birth. The iris (coloured part of the eye) starts to develop at around week 4 to 5 and within 2 weeks, it will become fully developed.

At 8 weeks of pregnancy, the tear duct starts to develop and will become fully formed a few weeks after birth. Tear production reaches its full potential approximately 3 months after birth, which is why infants do not shed tears when they cry.

The second trimester (12 to 24 weeks)

At 12 weeks of pregnancy, the eyelids start to form. They protect the iris and lens and remain closed till about 27 weeks of pregnancy. After which, the eyes of the foetus open up and can blink in response to bright light from outside the womb.

The iris starts to develop at 5 weeks of pregnancy, but the ciliary muscles that control the pupil do not develop until 5 months of pregnancy. Since the environment of the womb is dark, the constriction of the pupil in response to light is not needed and hence only develops at around the 8th month of pregnancy. Because this reflex develops later in gestation (the period of development inside the womb), babies born before 34 weeks of pregnancy need eye protection, which is why premature babies wear eye coverings until the gestation period is complete.

The third trimester (24 to 40 weeks)

At 30 weeks of pregnancy, the pupils can react and control the amount of light that enters the eye.

Between 28 and 30 weeks of pregnancy, the foetus also begins to develop eye movements and sleep patterns. Signals from the retina match the brain waves and a disruption to these cycles or insufficient sleep can significantly interfere with visual development.

From 32 weeks till birth, the foetus can focus on large objects at about 20 to 25 centimetres away. Interestingly, since the colour of the uterus is red, the foetus now has enough cells to see their very first colour, red.

Most of the development of the retina occurs between 24 weeks of pregnancy and 3 to 4 months after birth. During this time, the optic nerve also receives a coating called myelin around the nerve in a process known as myelination, which allows accurate signal transmission to take place.

The development of the macula starts during the third trimester and matures at around 6 months after birth. As the retina and lens develop, the vitreous forms between them. Alongside it, connections between the eye and the brain also start to form, which takes about 5 months to complete.

A newborn’s vision

A newborn’s vision is about the same as the vision of a foetus at 36 weeks of pregnancy. From a newborn’s point of view, things are fuzzy for a while. Although the eyes can see, the brain isn’t ready to process all the visual information.

The ability to focus is still underdeveloped and visual acuity (the ability to discern shapes and details in objects) in infants is about 20/400 or 6/120. By 6 months of age, this improves to 20/25 or 6/7.5. This process is known as emmetropisation, where the length of the eyeball aims to match the power of the eye [1]. Emmetropisation completes at around 6 years of age [2]. Most infants have hypermetropia, where light rays focus beyond the retina instead of on the retina. Hypermetropia typically decreases to a low level by teenage years [2]. However, the process of emmetropisation differs among children and a disruption (a quicker lowering of hypermetropia and lengthening of the eyeball) to this process can result in an early onset of myopia, where light rays fall short (in front) of the retina.

A newborn’s eyes are approximately two-thirds of its full size. The rod cells are better developed at birth, allowing a newborn to see dark and light shades of grey. Colour recognition then begins at 3 months of age when the cone cells mature.

What does a child see as they grow?

Each child is unique and might reach certain milestones at different ages. The table below summarises several visual milestones that take place as children grow older. It is important to note that this table is only a guideline and should not be used to replace a consultation with a trained eye health professional. Uncorrected refractive errors like myopia, hypermetropia, and astigmatism, as well as other issues, if any, may affect general and visual development.

| AGE | VISUAL MILESTONES |

| Birth to 1 month | Blinks in response to light Able to stare at objects 20 to 25 centimetres away Begins to follow moving objects |

| 1 to 2 months | Clear vision at 25 to 50 centimetres away Able to stare at faces and distinguish black & white images Begins to develop tears |

| 2 to 5 months | Begins to notice familiar objects located 50 centimetres away Able to follows faces, objects, and light |

| 5 to 7 months | Develops full colour vision Able to turn the head to see objects |

| 7 to 12 months | Develops independent eye movements Able to notice smaller objects Development of depth perception Able to watch and follow fast moving objects |

| 1 to 1.5 years | Clear distance vision Able to perceive depth (depth perception) of objects Able to do refined eye movements |

| 1.5 to 2 years | Development of fine motor skills Able to draw straight lines or circles |

| 2 to 3 years | Improvement of convergence and focusing abilities Able to change focus from distant to near vision, as well as near to distant vision Improvement of depth perception |

| 3 to 4 years | Vision at far is about 20/20 or 6/6 Able to recognise complex visual shapes and letters |

| 4 to 6 years | Clear vision at all distances |

Frequently asked questions (FAQs)

Q: When should my child have their first eye exam?

A: They should have their first comprehensive eye check at 6 months of age, even if no eye or vision problems are apparent. If there are any hereditary eye conditions, the first comprehensive eye exam could be earlier than 6 months of age or as recommended by an eye health professional.

Q: What should I take note of if my infant is premature?

A: The eyes of an infant born prematurely will be examined by a specialist soon after birth to rule out any common eye conditions like cataract, infantile glaucoma, and eye tumours.

Q: How do I know if there is something wrong with my child’s eyes before 6 months of age?

A: Watch for signs of vision problems, for example, if you think your child may not be responding to their environment appropriately or if you notice that your child is not reaching an important visual developmental milestone, schedule an eye check with an eye health professional at your earliest convenience.

Q: How often should I bring my child for an eye check?

A: There are general guidelines for eye checks available that differ between countries and it is advised to check with your country’s framework. The American Academy of Ophthalmology recommends:

• Once between 6 to 12 months old

• Once between 3 to 3.5 years of age

• At schooling age, once every 1 to 2 years. It should be noted that a vision test commonly done at schools is a screening tool and does not replace a comprehensive eye check.

Q: What are some common eye complications that can occur in infants/toddlers?

A:

• Excessive tearing, which may suggest blocked tear ducts

• Red or crusty lids, which may suggest an eye infection

• Constant eye turning, which may be a problem with eye muscle control and suggestive of strabismus

• Extreme sensitivity to light, which may indicate an abnormally high pressure in the eye, also known as glaucoma

• Appearance of a white pupil, which may indicate a form of eye cancer known as retinoblastoma

Q: How much screen time is recommended for young children?

A: Here are some recent screen time guidelines according to the World Health Organization

• Infants younger than 1 year old: Not recommended

• Children 1 to 2 years old: Not recommended

• Children 2 to 4 years old: Sedentary screen time should not be more than 1 hour each day

Note: For children of all ages, when sedentary, reading and storytelling with a caregiver is encouraged

Q: What can a child see at birth?

A: A newborn’s vision is fuzzy. They can see dark and light shades of grey, blink in response to light, and begin to follow moving objects. The ability to focus is still underdeveloped and visual acuity in infants is only about 20/400 or 6/120.

Q: What do I do if I notice my child has a turned eye?

A: Inform your child’s doctor (paediatrician) and if necessary, they will refer your child to an eye doctor (ophthalmologist) to assess and treat the turned eye.

Q: What are the signs of poor vision in a child?

A: If one eye turns or crosses, it could mean that vision is worse in that eye. Another sign to look out for is if a child is not interested in faces or age-appropriate toys. Tilting their head and frequently squinting their eyes in an attempt to see their surroundings clearly is another sign that a child might have vision problems. Infants and children may not be able to express that they have poor vision so it is important for parents and caregivers to look out for these signs and ensure that they have regular and timely eye checks.

DISCLAIMER: THIS WEBSITE DOES NOT PROVIDE MEDICAL ADVICE

The information, including but not limited to, text, graphics, images and other material contained on this website are for informational purposes only. No material on this site is intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis or treatment. Always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified healthcare provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition or treatment and before undertaking a new healthcare regimen, and never disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something you have read on this website.

References

[1] C. F. Wildsoet, “Active emmetropization–evidence for its existence and ramifications for clinical practice.,” Ophthalmic Physiol. Opt. J. Br. Coll. Ophthalmic Opt., vol. 17, no. 4, pp. 279–290, Jul. 1997.

[2] D. I. Flitcroft, “Emmetropisation and the aetiology of refractive errors.,” Eye (Lond)., vol. 28, no. 2, pp. 169–179, Feb. 2014, doi: 10.1038/eye.2013.276.

[3] L. Conlin, “Embryonic eye development,” Embryonic Eye Development, Dec-2012. [Online]. Available:https://bt.editionsbyfry.com/article/Embryonic_Eye_Development/1251148/137190/article.html. [Accessed: 28-Jul-2021].

[4] “Infant vision development: What can babies see?,” HealthyChildren.org, May-2016. [Online]. Available:https://www.healthychildren.org/English/ages-stages/baby/Pages/Babys-Vision-Development.aspx. [Accessed: 28-Jul-2021].

[5] H. E. Murkoff, S. Mazel, and M. D. Widome, What to expect the first year. London: Simon & Schuster, 2018.

[6] “Infant vision: Birth to 24 months of age,” American Optometric Association. [Online]. Available: https://www.aoa.org/healthy-eyes/eye-health-for-life/infant-vision?sso=y. [Accessed: 28-Jul-2021].

[7] D. Gudgel, “Eye screening for children,” American Academy of Ophthalmology, 23-Mar-2021. [Online]. Available:. [Accessed: 28-Jul-2021].

Tools Designed for Healthier Eyes

Explore our specifically designed products and services backed by eye health professionals to help keep your children safe online and their eyes healthy.