What is a retinal detachment?

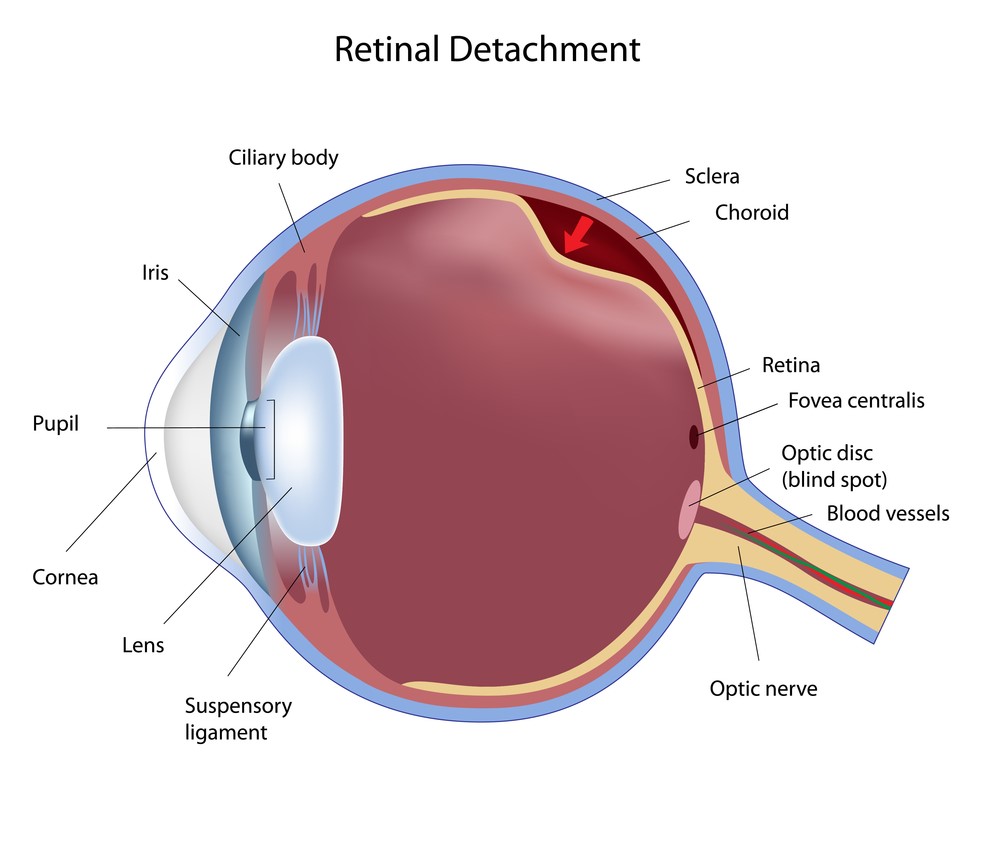

A retinal detachment is a vision threatening condition whereby the neurosensory retina, the internal lining of the eye responsible for transmitting light signals, comes away from its underlying structures, such as the retinal pigment epithelium (layer of pigmented cells at the retina).

This detachment allows for an accumulation of fluid to occur between these layers and can occur via 3 mechanisms:

- Rhegmatogenous: fluid comes through via a retinal tear. If this type of detachment is left untreated, it can progress rapidly and lead to blindness

- Tractional: bands of scarred tissue that lift the retina (more common in diabetics)

- Serous: where fluid accumulates but there is no tear in the retina. This type of detachment does not always necessitate surgery

This overview will cover how common is retinal detachment, who are at risk, the symptoms of retinal detachment, how it is detected, the available treatment options, as well as the possible prevention methods.

How common is retinal detachment?

Retinal detachments affect about 1 in 10,000 people in the world [1]. Ethnic variations exist and it is well known that a patient of Chinese origin is 3 times more likely to need retinal detachment surgery compared to their Indian counterparts [2]. There are reports that some developing countries have a lower rate of new cases of retinal detachment; however, due to poor access to facilities and delayed detection and management of the condition, the risk of blindness is higher in this group of people [2].

Who is at risk of retinal detachments?

The risk factors for a retinal detachment can be divided into those that are associated with patient (lifestyle) factors and anatomical (due to other eye conditions) factors [3].

Patient/lifestyle factors include:

- Increasing age

- Trauma

- Previous retinal detachment

- Previous intraocular surgery

- Family history

Factors due to other eye conditions include:

- Myopia (short-sightedness)

- Retinal tears

- Lattice degeneration (areas of thinned retina)

Of these, myopia, lattice degeneration, and increasing age are most strongly associated with retinal detachments [3]. Patients can find out if they are at risk due to other eye conditions by booking an appointment with a local optometrist for a dilated retinal examination.

What are the symptoms of a retinal detachment?

The classic symptoms of a retinal detachment are new onset (development) floaters, flashes, as well as possibly a curtain-like shadow in the peripheral (outer) vision. If the macula (part of the retina at the back of the eye responsible for central vision) is involved, then the central vision will be perceived as blurred. Rarely, a retinal detachment may exist for a long time in the eye but the patient may not show any symptoms.

If you experience any of these signs and symptoms, schedule an appointment with an eye health professional to get your eyes checked. It is also important to note that the development of eye conditions may even start before symptoms appear, which makes going for regular and timely eye checks that much more essential.

How is a retinal detachment detected?

A retinal detachment is detected by using a special lens and a slit lamp to examine the retina. The patient has mydriatic (dilating) drops instilled to expand the pupil, which subsequently facilitates visualisation of the retina. Special contact lenses and ancillary equipment called an indenter may be used to bring the peripheral retina into view for the examiner to aid in identifying a break in the retina.

What are the treatment options for a retinal detachment?

Retinal detachments, particularly those of a rhegmatogenous nature, require urgent treatment. If the macula is involved, treatment ideally should be performed within 24 to 72 hours upon diagnosis. If the macula is not involved, then treatment may be performed within 7 to 10 days upon diagnosis as earlier treatment has not been shown to improve visual outcomes [4].

The goal of repair in a rhegmatogenous detachment is to identify the break and treat it. Treatment options depend on patient factors and the nature of the detachment. Several options available to treat retinal detachments are [4], [5]:

- Pars plana vitrectomy

- Pneumatic retinopexy

- Scleral buckle

Pars plana vitrectomy

This procedure involves insertion of ports to access the internal cavity of the eye. The vitreous is removed using specialised instruments and a thorough search is performed to find the retinal break. Subretinal fluid is removed from the retina and a tamponade such as gas or oil is inserted to keep the retina placed and fixed in close proximity [5].

Pneumatic retinopexy

Some patients may be suitable candidates for this procedure, which involves the injection of a gas bubble into the eye. The criteria for treatment with pneumatic retinopexy varies but are suited when there is a good view to the retina, a single break in a superior position, and the patient is able to position their head as required by the surgeon [5]. In some centres, this procedure can be performed in an outpatient, rather than an operation theatre, setting.

Scleral buckle

A scleral buckle is a silicone band that is inserted around the eye and is positioned underneath the extraocular muscles. The buckle relieves the traction and flattens the retina and an adjunctive cryotherapy or laser is often administered [5].

Treatment of tractional retinal detachments follows similar principles as treating rhegmatogenous detachments with the aim being to relieve tractional bands via pars plana vitrectomy. Adjunctive scleral buckles may also be used. Serous retinal detachments are not treated surgically and its treatment is aimed at addressing the underlying issue such as inflammation [5].

Is it possible to prevent retinal detachments?

Most retinal detachments occur without any clear and sudden cause but those at higher risk such as patients with myopia, may consider the use of protective eyewear when undergoing contact sports. Ultimately, if detected and treated early and patients only present themselves with new symptoms (floaters and flashes), it is possible that the tear can be treated with laser retinopexy before it progresses into a retinal detachment.

DISCLAIMER: THIS WEBSITE DOES NOT PROVIDE MEDICAL ADVICE

The information, including but not limited to, text, graphics, images and other material contained on this website are for informational purposes only. No material on this site is intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis or treatment. Always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified healthcare provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition or treatment and before undertaking a new healthcare regimen, and never disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something you have read on this website.

References

- D. A. Brinton and C. P. Wilkinson, “Pathogenesis, Epidemiology, and Natural Course of Retinal Detachment,” Retinal Detachment. 2009. doi: 10.1093/oso/9780195330823.003.0006.

- D. Yorston and S. Jalali, “Retinal detachment in developing countries,” Eye, vol. 16, no. 4. pp. 353–358, 2002. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6700188.

- D. Mitry, D. G. Charteris, B. W. Fleck, H. Campbell, and J. Singh, “The epidemiology of rhegmatogenous retinal detachment: geographical variation and clinical associations,” Br. J. Ophthalmol., vol. 94, no. 6, pp. 678–684, Jun. 2010.

- R. Scott and G. Kirkby, “Treatment of macula-on retinal detachments,” Eye, vol. 21, no. 7. pp. 1008–1008, 2007. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6702810.

- A. J. Brucker and T. B. Hopkins, “Retinal detachment surgery: the latest in current management,” Retina, vol. 26, no. 6 Suppl, pp. S28–33, Jul. 2006.